This post was originally featured on Ocean Health Index, a project of the National Center for Ecological Analysis and Syntheis. You can view the original post here

When You Think of a Border, What Comes to Mind?

The line drawn between countries? The landmass of a continent? The nested pieces of county or province lines? All of these things represent different ways nations have attempted to define borders. Borders serve as physical and ideological boundaries that shape the flow of goods, ideas, and people across a landscape [1]. For many, borders may seem like immutable attributes of our day-to-day life, as definite as the rest of the laws and customs that compose our individual societies. Yet for others, borders are muddied, complex constructs that arise from a long—and often violent—legacy of competing interests. While modern society may have rigorous definitions of what constitutes a border, they have come in many forms throughout human history.

“Territorial borders both shape and are shaped by what they contain, and what crosses or is prevented from crossing them.” - James Anderson & Liam O’Dowd [2]

The first borders were natural. A mountain range or a river served as a geographic barrier between different species, biogeochemical processes, peoples, and more [3]. The first anthropogenic borders, however, are thought to have originated with the dawn of agriculture [4]. Settlement meant that people needed a way to clearly demarcate land for crop cultivation, storage, and livelihood. At the same time, this is where some of the first notions of private property were established [4]. To draw a line between you and your neighbor meant an assertion of ownership and a partitioning of land into divisible parts. These ideas of land ownership and borderlines would move hand in hand throughout human history, playing a role in the rise and fall of different tribes, empires, and states up to and including modern day.

Nowadays, a border is a politically defined line that represents an area of sovereignty between different geographic regions [5], [6]. Borders play a large role in constructing our everyday life; they define where we call home and shape how we relate to the rest of the world. In the Ocean Health Index, borders at sea are foundational to how we calculate the global score. But where do these borders come from and how do they shape the way we imagine ocean health at regional and global scales?

Borders at Sea

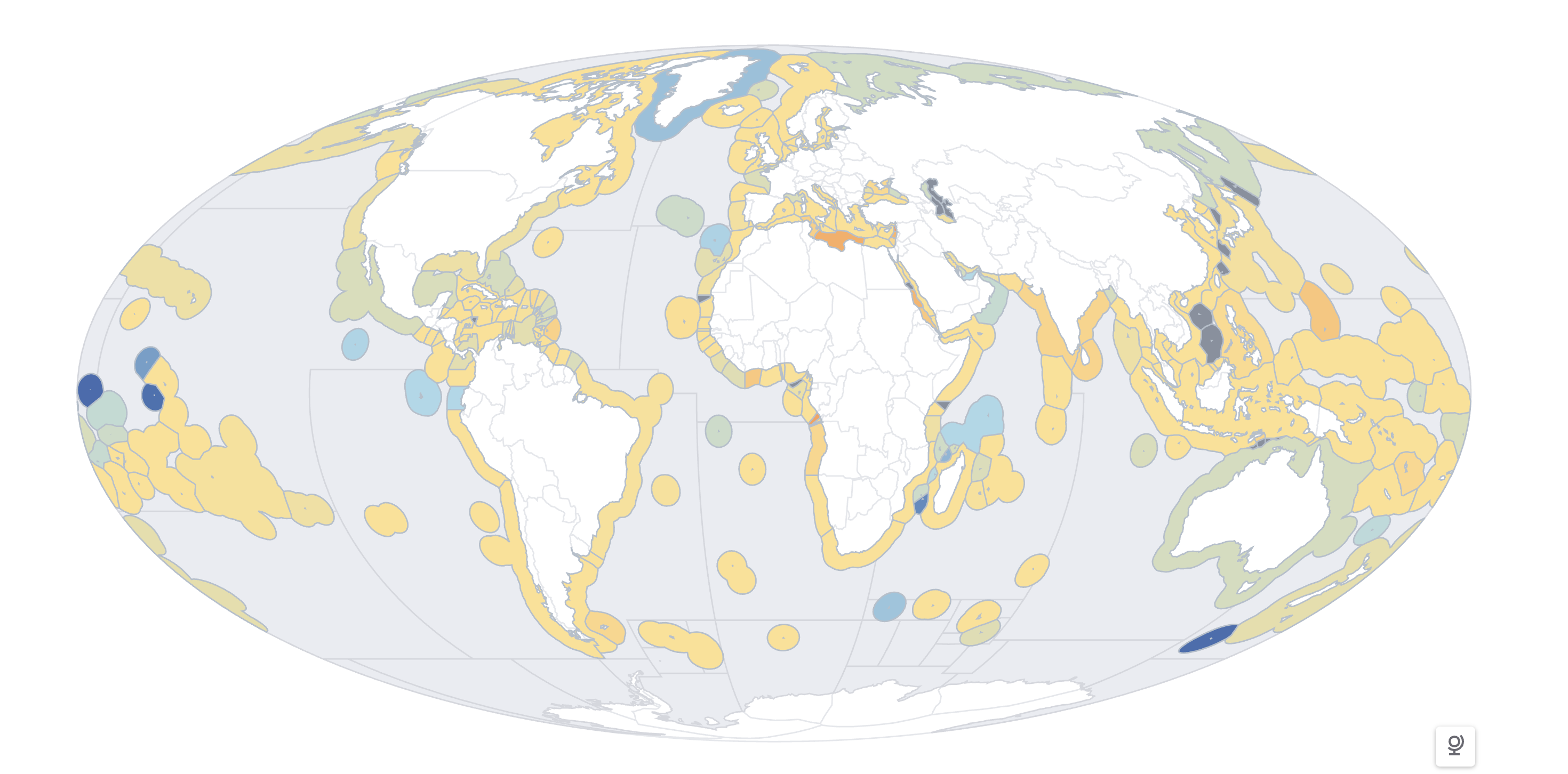

Borders at sea, or maritime boundaries, are the politically defined lines that partition the ocean and its resources into different national jurisdictions. When you view the map of OHI global scores, you’ll notice that each region has a distinct boundary along its coastline that indicates the sovereign waters of that nation. This boundary is referred to as the Exclusive Economic Zone, or EEZ. The EEZ is a 200 nautical mile area off a nation’s coastline where the state has jurisdiction over coastal resources. More specifically, it’s where a nation has the right to explore, manage, conserve, and exploit natural resources in the sea and seabed [7]. The EEZ has become the international standard for the governance of marine resources, but that hasn’t always been the case. Let’s explore the political origins of the EEZ.

A global map of Exclusive Economic Zones, colored by OHI score

The EEZ: a Short and Sweet History

Maritime boundaries are historically even more nebulous than their terrestrial counterparts. While it is possible to define landmasses with fences or walls, there is no easy solution to drawing lines at sea. Furthermore, the concept of ownership of marine waters arose much later in political history than land ownership. One of the first sovereign claims to seabed resources was made in the 1945 United States presidential proclamation [8], which asserted jurisdictional control over natural resources on the continental shelf—the area of seabed around a landmass where the water is relatively shallow. Happening concurrently was the creation of Exclusive Fishery Zones (EFZ) in parts of Latin America. In 1947, Chile and Peru declared a 200 nautical mile (nm) zone off the coast where they would control marine resources and maintain navigational rights [9]. This 200nm zone would become the foundation for the EEZ we know today.

Over the next 30 years, a multitude of laws across Latin America, Asia, and Africa would be created that further refined a country’s jurisdictional rights regarding marine and coastal resources [9]. These declarations touched on many aspects of coastal law: from seabed and seafloor resources, to prioritizing conservation efforts, to asserting the interests of landlocked states. All of these would become foundational for the definitive creation of a formal Exclusive Economic Zone in the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea.

The UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, or UNCLOS, is a comprehensive international treaty that established a legal framework for all activities in the world’s oceans and seas [10]. Broadly speaking, the UNCLOS defined maritime boundaries at multiple scales, established international governing bodies, and outlined rights and responsibilities of participating states [11]. The UNCLOS has become the definitive authority for laws and regulations concerning global oceans and the resources contained therein.

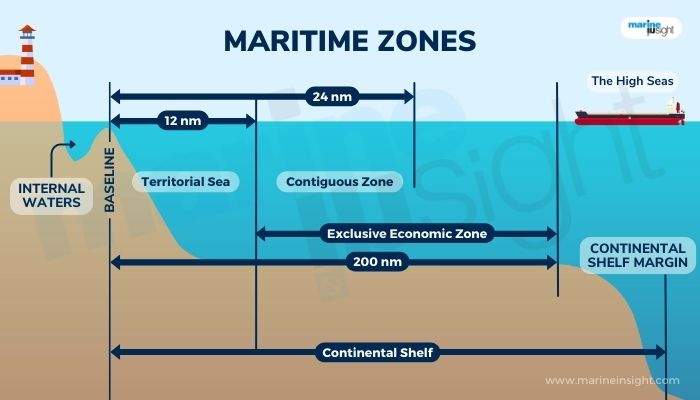

The EEZ boundary you see in the OHI global map comes from the maritime zones defined in the UNCLOS. There are several zones included in the definition, including the territorial sea that extends 12nm from the coast, the EEZ that extends 200nm, and the high seas past 200nm free from any national jurisdiction [9].

UNCLOS Maritime Zones (source)

Disputed Territories

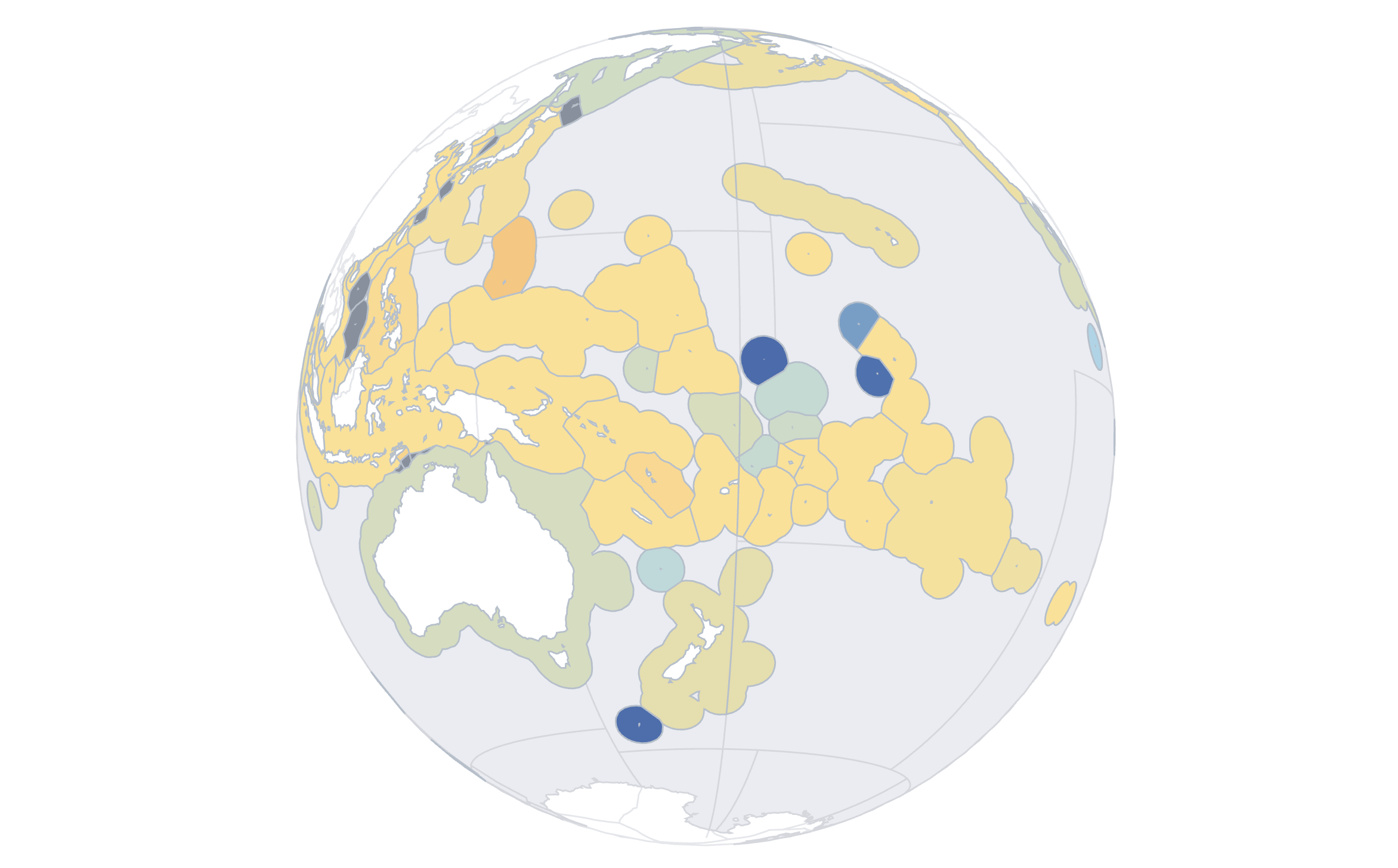

While the UNCLOS made great strides in unifying global consensus around maritime boundaries, the EEZ was not a one-size-fits-all solution. What happens when the EEZ borders of two sovereign nations overlap? How do you manage declining fish populations with unequal distribution across political lines? These are just a few examples of the conflicts that can lead to a border dispute, or a disagreement between different political actors over the precise location or ownership of a particular geographic boundary [12], [13]. These border disputes occur all over the world and are often tense, complex, and ever-changing phenomena. In the OHI framework, they show up as disputed territories, or regions shaded gray on the global score map.

Overlapping EEZs in Oceania and Southeast Asia

Maritime Boundaries in a Changing Climate

As climate change continues to drive our ecosystems towards extremes, these border disputes are only going to increase in frequency. Sea-level rise is already beginning to physically redraw coastlines, changing the baselines from which the maritime zones are measured and thus their overall size [14]. And as low-lying islands shrink—or even disappear—questions arise about whether their EEZs persist, contract, or vanish altogether. Meanwhile, shifting fish stocks and migratory patterns driven by warming oceans are already altering the distribution of vital resources, putting additional pressure on existing boundaries [15]. In the Arctic, melting ice is opening new navigable passages and exposing untapped resources, leading to a flurry of jurisdictional claims [16].

These tensions underscore that maritime boundaries are just as fluid as the seas they attempt to define, and the dynamic nature of our marine ecosystems is going to test the socio-political structures we have constructed around them.

To manage these pressures, states have turned to a mix of bilateral treaties, international arbitration, and joint-development agreements [17]. Bodies like the International Court of Justice and the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea have helped resolve disputes through legal rulings, while joint resource-sharing pacts allow countries to avoid escalation while still benefiting economically [18]. These solutions highlight that cooperation, rather than unilateral assertion, is often the most sustainable path forward [19].

So far, we’ve seen that boundaries change for a number of reasons—political, economic, ecological. But what do these shifting maritime boundaries mean for the Ocean Health Index? Because scores are calculated within the framework of EEZs, the implications are significant. Any shift in boundaries reshapes how we measure a nation’s performance. A country’s apparent progress or decline may reflect not just ecological realities but also the way its maritime borders are defined. In this sense, the fluidity of boundaries directly influences our understanding of ocean health and stewardship, reminding us that the environment cannot be divorced from the political and social frameworks in which it is embedded.

Beyond Ownership

The discussion of borders, both terrestrial and marine, rests on one vital assumption: that land and sea are things that can be owned. The concept of private property is a deeply ingrained framework of modern society, so much so that its legitimacy is almost never called into question. Yet, it is not the only frame with which people have imagined their relationship to the Earth. Indigenous nations around the world have long held a different perspective on land-relations, centering care and stewardship of natural spaces in the same way one might care for a loved one [20].

Across the globe, Indigenous ocean stewardship offers powerful examples of alternatives to ownership-based management. In Hawai‘i, traditional stewardship practices offer a vivid reminder that the ocean can be managed through care rather than control. Systems such as the kapu placed strict, seasonal restrictions on harvesting certain fish species, allowing populations to recover and ensuring abundance for future generations [21]. These rules are deeply cultural, rooted in respect for the ocean as a living relative rather than a resource to be managed. Today, Hawaiian communities are revitalizing these practices through community-based subsistence fishing and co-management programs that blend Indigenous knowledge with modern science [22].

As rising seas, shifting resources, and contested EEZs reshape the map, the Ocean Health Index will need to adapt, incorporating changing borders while also recognizing that boundaries are only one way to measure human-ocean relationships. By engaging with alternative frames of stewardship, we open the door to different results, ones that may highlight resilience, equity, and sustainability beyond the limits of political lines.

References

Citation

@online{oyler2025,

author = {Oyler, Haylee},

title = {A {Line} in the {Sand:} {What} {Makes} a {Maritime}

{Boundary?}},

date = {2025-09-03},

url = {https://haylee360.github.io/posts/2025-09-03-borders/},

langid = {en}

}